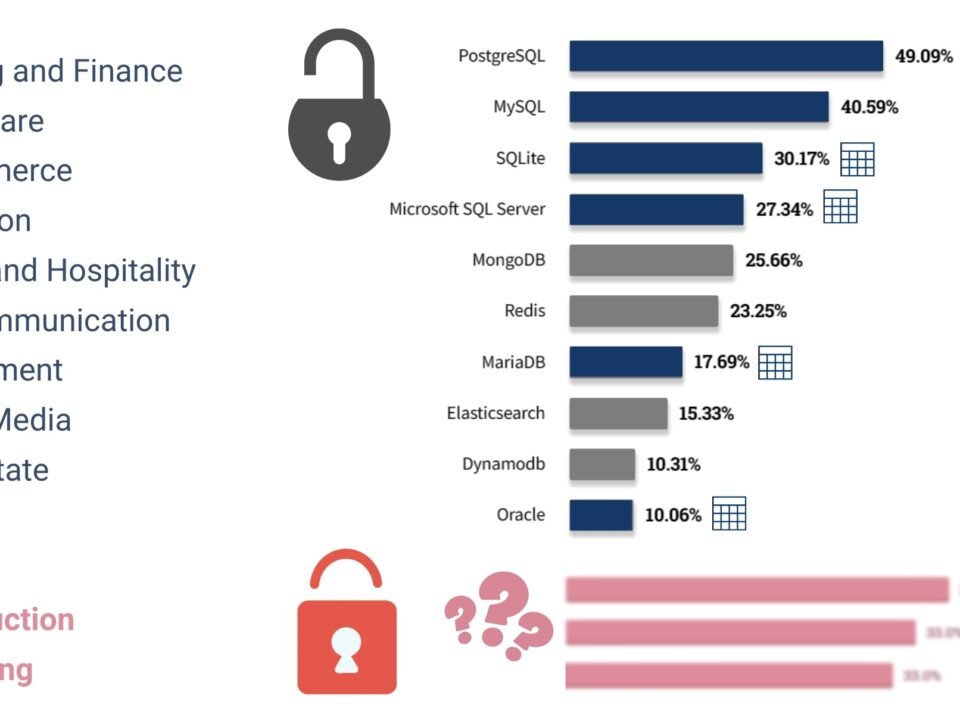

The construction industry is undergoing a shift that cannot be monetized in the usual way. The concept of data-driven, data-centric approach and the use of Open Source tools is leading to a rethinking of the rules of the game on which the software giants of the market stand.

Unlike previous technology transformations, this transition will not be actively promoted by vendors. The paradigm shift threatens their traditional business models based on licensing, subscriptions and consulting. The new reality does not involve an out-of-the-box product or a paid subscription – it requires a re-engineering of processes and thinking.

To manage and develop data center solutions based on open technologies, companies will need to rethink internal processes. Specialists from different departments will have to not only collaborate, but also rethink how they work together.

The new paradigm implies the use of open data and Open Source solutions, where tools based on artificial intelligence and large language models (LLM) rather than programmers will play a special role in creating program code. Already by mid-2024, more than 25% of new code at Google is created with AI (The Verge, “More than a quarter of new code at Google is generated by AI,” October 29, 2024). In the future, coding with LLMs will do 80% of the work in just 20% of the time (Fig. 3.2-14).

According to McKinsey’s 2020 study (McKinsey Digital, “The business case for using GPUs to accelerate analytics processing,” December 15, 2020), GPUs are increasingly replacing CPUs in analytics due to their high performance and support by modern Open Source tools. This allows companies to accelerate data processing without significant investments in expensive software or hiring scarce specialists.

Leading consulting firms such as McKinsey, PwC and Deloitte emphasize the growing importance of open standards, Open Source applications across industries.

According to the PwC Open Source Monitor 2019 report (PWC, “PwC Open Source Monitor 2019,” 2019), 69% of companies with 100 or more employees consciously use Open Source solutions. OSS is especially actively used in large companies: 71% of companies with 200-499 employees, 78% in the 500-1999 employee category, and up to 86% among companies with more than 2000 employees. According to the Synopsys OSSRA 2023 report, 96% of the analyzed codebases contained open source components(Travers Smith, “The Open Secret: Open Source Software,” 2024).

The future of the developer’s role is not to manually write code, but to design data models, flow architectures, and manage AI agents that create the right calculations on demand. User interfaces will become minimalistic and interaction will become dialog-based. Classical programming will give way to high-level design and orchestration of digital solutions (Fig. 3.2-14). Current trends – such as low-code platforms (Fig. 7.4-6) and LLM-enabled ecosystems (Fig. 7.4-4) – will significantly reduce the cost of developing and maintaining IT systems.

This transition will be unlike previous ones and the big software vendors will likely not catalyze it.

Harvard Business School study “The Value of Open Source Software” 2024 (F. N. a. Y. Z. Harvard Business School: Manuel Hoffmann, “The Value of Open Source Software,” 24 Jan. 2024), the total value of open source software is estimated from two points of view. On the one hand, if we calculate how much it would take to build all existing Open Source solutions from scratch, this amount would be about 4.15 billion dollars. On the other hand, if we imagine that each company develops its own analogs of Open Source solutions on its own (which happens everywhere), without having access to existing tools, then the total cost of business would reach a colossal 8.8 trillion dollars – this is the cost of demand.

It’s not hard to guess that no major software vendor is interested in shrinking a software market with a potential value of $8.8 trillion to just $4.15 billion. This would mean reducing the volume of demand by more than 2,000 times. Such a transformation is simply unprofitable for vendors whose business models are built on years of maintaining customer dependence on closed solutions. Therefore, companies expecting someone to offer them a convenient and open turnkey solution may be disappointed – such vendors simply won’t show up.

The shift to an open digital architecture does not mean job or revenue losses. On the contrary, it creates the conditions for flexible and adaptive business models that may eventually displace the traditional license and boxed software market.

Instead of selling licenses – services, instead of closed formats – open platforms, instead of dependence on a vendor – independence and the ability to build solutions for real needs. Those who used to simply use tools will be able to become their co-authors. And those who can work with data, models, scenarios and logic will find themselves at the center of the industry’s new digital economy. We will talk more about these changes and what new roles, business models, and collaboration formats are emerging around open data in the final, tenth part of the book.

Solutions based on open data and open code will allow companies to focus on the efficiency of business processes rather than on struggling with outdated APIs and integrating closed systems. A conscious transition to open architecture can significantly increase productivity and reduce dependence on vendors.

The transition to a new reality is not just a change in approaches to software development, but also a rethinking of the very principle of working with data. At the center of this transformation is not code, but information: its structure, accessibility and interpretability. And this is where open and structured data comes to the forefront, becoming an integral part of the new digital architecture.