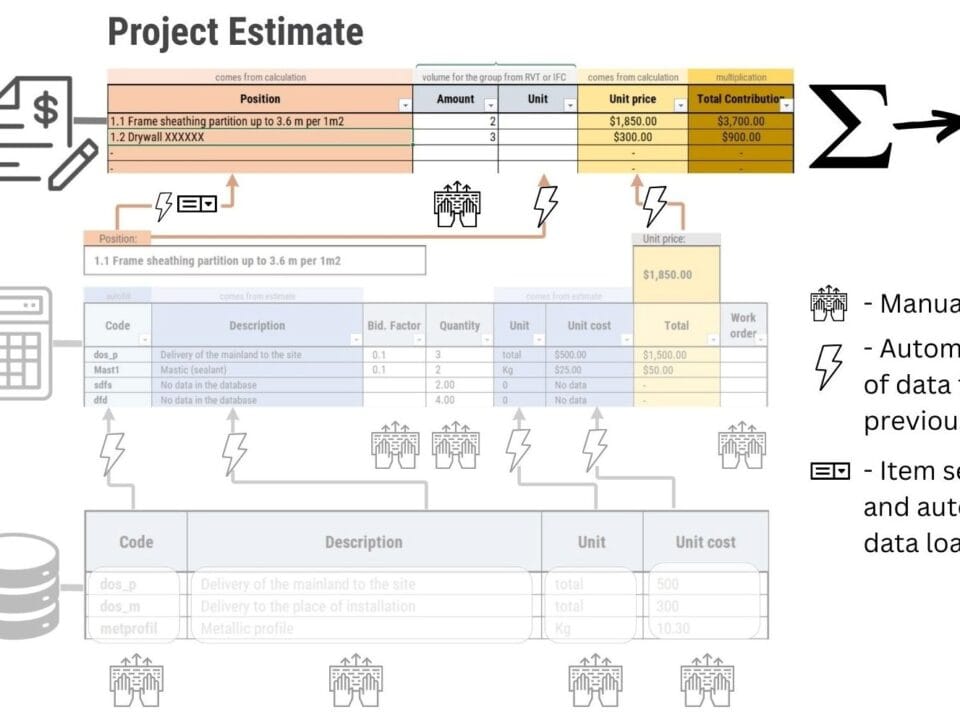

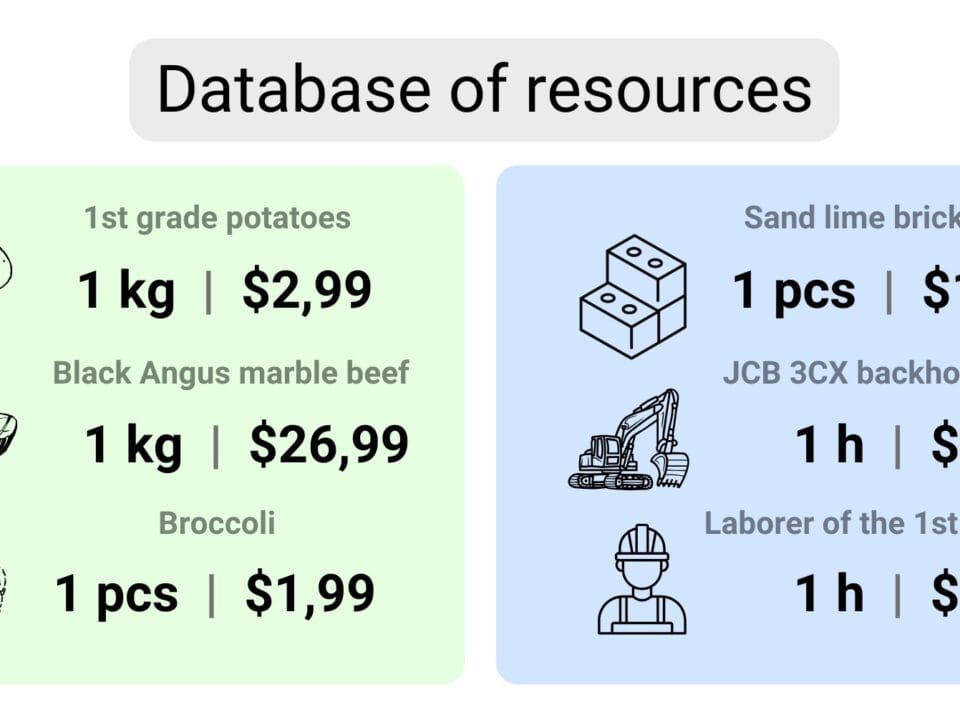

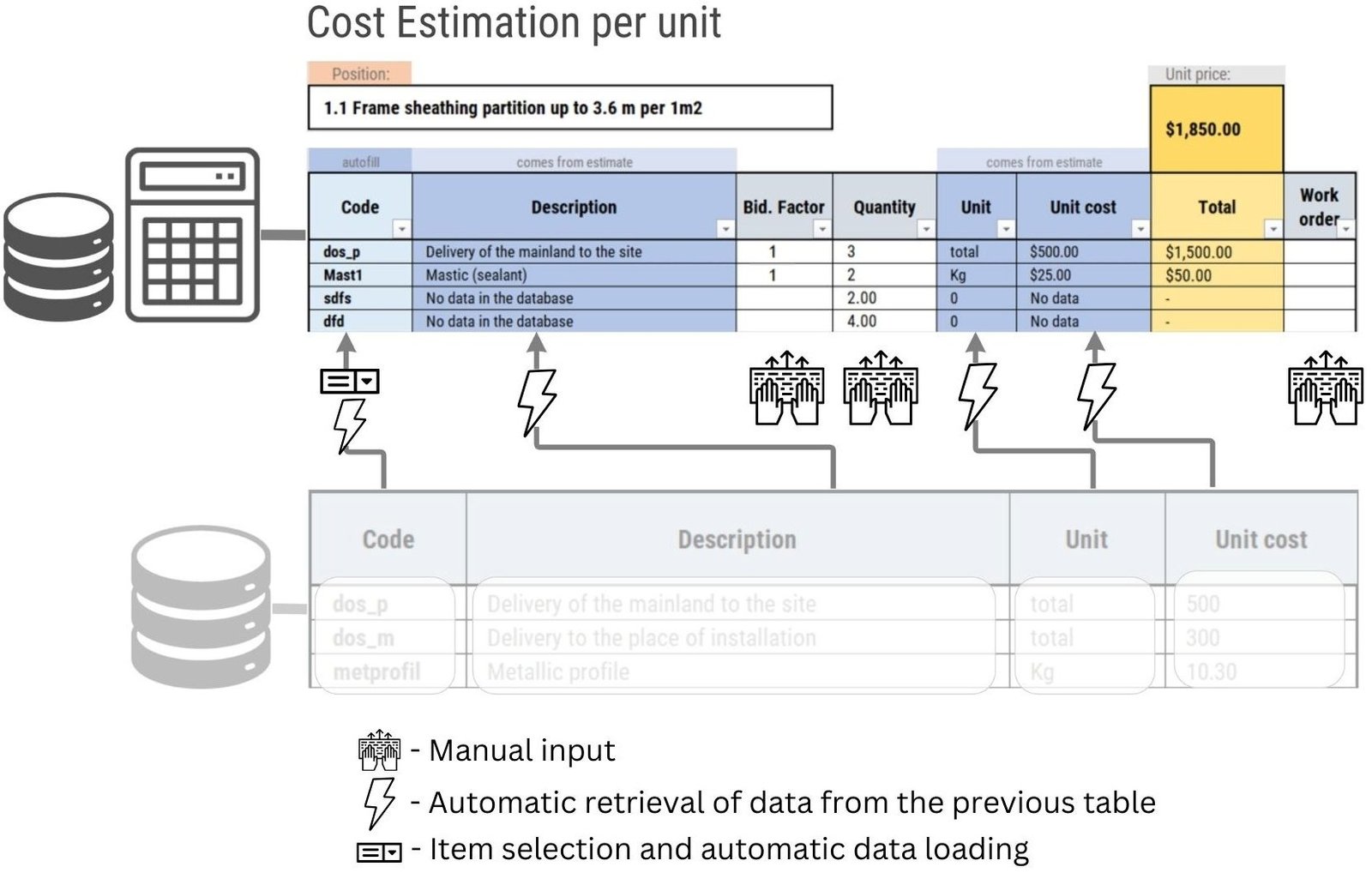

Having filled the “Construction Resource Database” (Fig. 5.1-3) with entities-minimum units, you can start creating calculations, which are calculated for each process or work on the construction site for certain units of measurement: for example, for one cubic meter of concrete, one square meter of drywall, one meter of curb or one window installation.

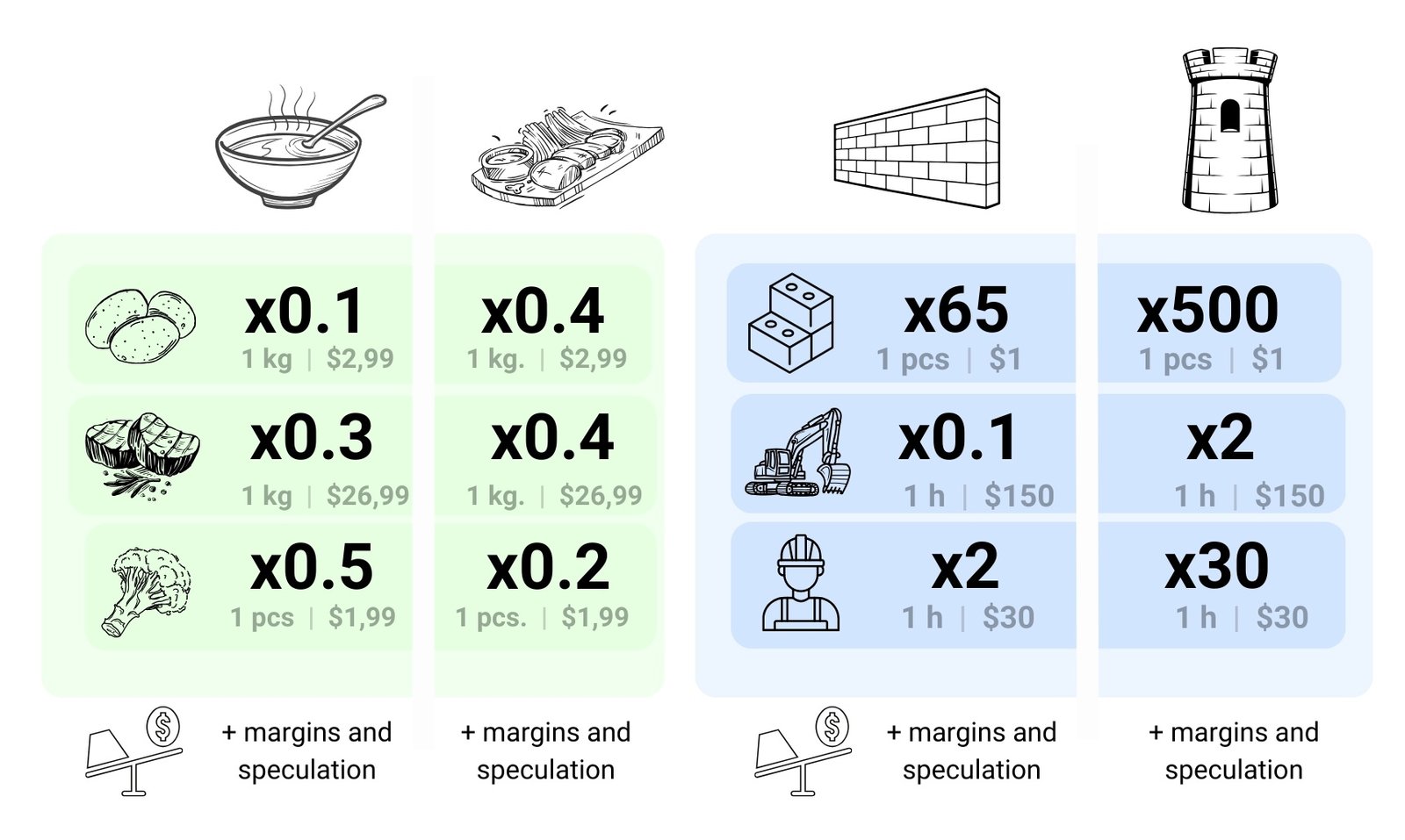

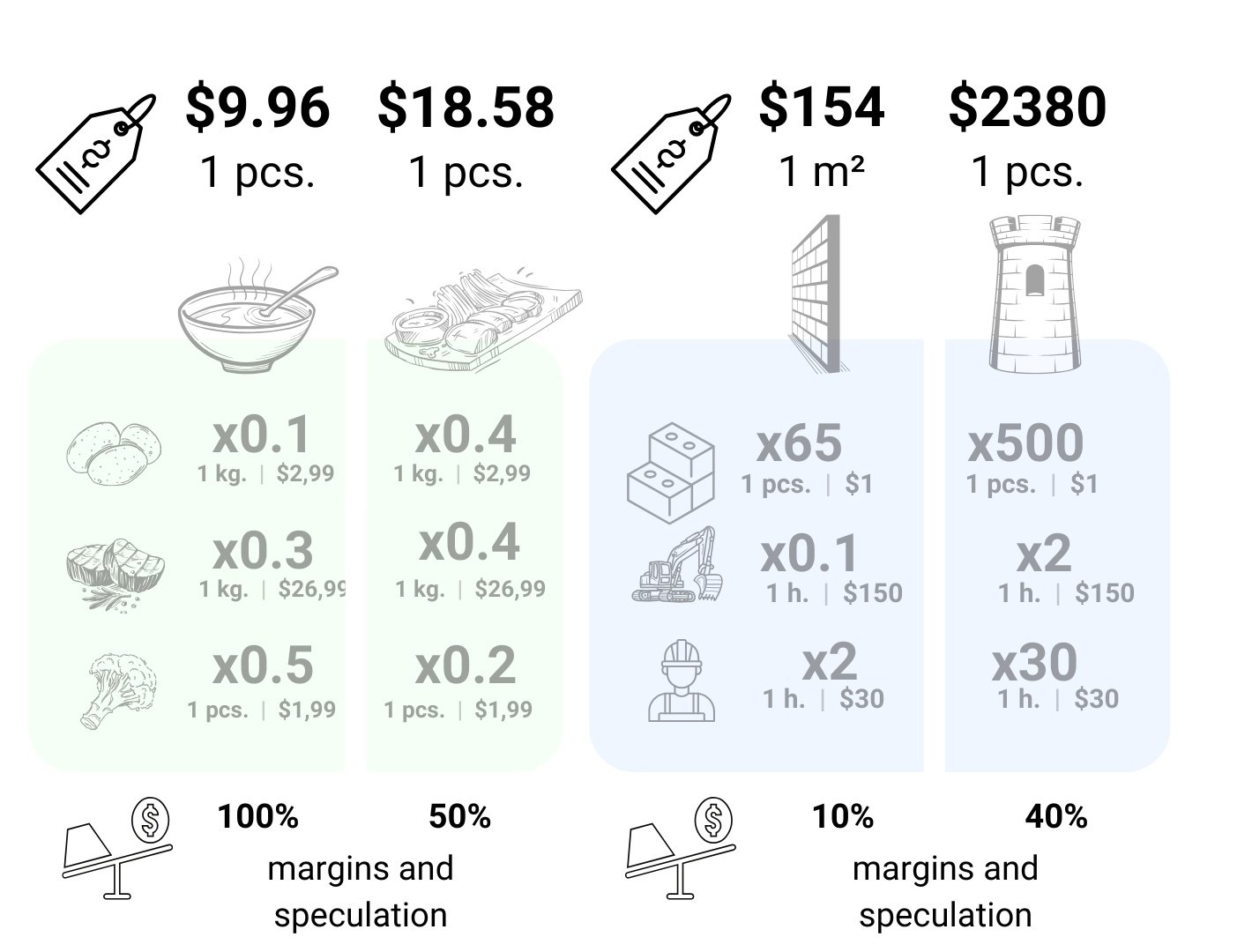

For example, to build a 1 m² brick wall (Fig. 5.1-4), based on experience from previous projects, approximately 65 bricks (entity “Silicate Brick”) are required at a cost of $1 per piece (attribute “Cost per piece”), totaling $65. Also, in my experience, it is required to use construction equipment (entity “JCB 3CX Loader”) for 10 minutes that will place bricks near the work area. Since it costs $150 per hour to rent the equipment, 6 minutes of use would cost approximately $15. In addition, a brick-laying contractor will be needed for 2 hours, with an hourly rate of $30 and a total of $60.

The composition of calculations (so-called “recipes”) is formed on the basis of historical experience accumulated by the company in the process of performing a large volume of similar work. This practical experience is usually accumulated through feedback from the construction site. In particular, the foreman collects information directly at the construction site, recording actual labor costs, material consumption and nuances of technological operations. Then, in collaboration with the estimating department, this information is iteratively refined: process descriptions are refined, resource mix is adjusted, and cost estimates are updated to reflect actual data from recent projects.

Just as a recipe describes the necessary ingredients and quantities to prepare a dish, an estimate sheet provides a detailed list of all construction materials, resources, and services required to perform a particular job or process.

Regularly performed work allows workers, foremen and estimators to orient themselves in the necessary amount of resources: materials, fuel, working time and other parameters required to perform a unit of work (Fig. 5.1-5). These data are entered into the estimating systems in the form of tables, where each task and operation is described through the minimum elements of the resource base (with constantly updated prices), which ensures the accuracy of calculations.

To obtain the total cost of each process or work (costing object), the cost attribute is multiplied by its quantity and factors. The coefficients can take into account various factors such as complexity of the work, regional characteristics, inflation rate, potential risks (expected percentage of overhead) or speculation (additional profit factor).

The estimator, as an analyst, converts the experience and recommendations of the foreman into standardized estimates, describing construction processes through resource entities in tabular form. In fact, the estimator’s task is to collect and structure through parameters and coefficients the information coming from the construction site.

Thus, the final cost per unit of work (e.g., square or cubic meter, or one installation of one unit) includes not only the direct costs of materials and labor, but also company markups, overhead, insurance, and other factors (Fig. 5.1-6)

At the same time, we no longer have to worry about the actual prices in (recipe) calculations, because the real prices are always reflected in the “resource base” (ingredient table). At the level of calculations in the table automatically (e.g. by item code or its unique identifier) are loaded from the resource base, which uploads the description, and the actual cost per unit, which in turn can be automatically loaded from online platforms or online store of building materials. The estimator at the costing level of the work only has to describe the work or process through the attribute “quantity of resources” and additional factors.

The created cost estimates are stored in the form of template tables of standard projects, which are directly linked to the database of construction resources and materials. These templates represent standardized recipes for repetitive types of work for future projects, ensuring uniformity in calculations across the company.

When the cost of any resource changes in the database (Fig. 5.1-3) – whether manually or automatically via download of current market prices (e.g. in inflationary conditions) – the updates are immediately reflected in all linked costings (Fig. 5.1-6). This means that only the resource base needs to be changed, while the costing templates and estimates remain unchanged over time. This approach ensures the stability and reproducibility of the calculations for any price fluctuations, which are only accounted for in a relatively simple resource table (Fig. 5.1-3).

For each new project, a copy of the standard costing template is created, which makes it possible to make changes and adjust activities to meet specific requirements without changing the original template adopted by the company. This approach provides flexibility in adapting calculations: it is possible to take into account the specifics of the construction site, the customer’s wishes, to introduce risk or profitability (speculation) coefficients – and all this without violating the company’s standards. This helps the company find a balance between profit maximization, customer satisfaction and maintaining its competitiveness.

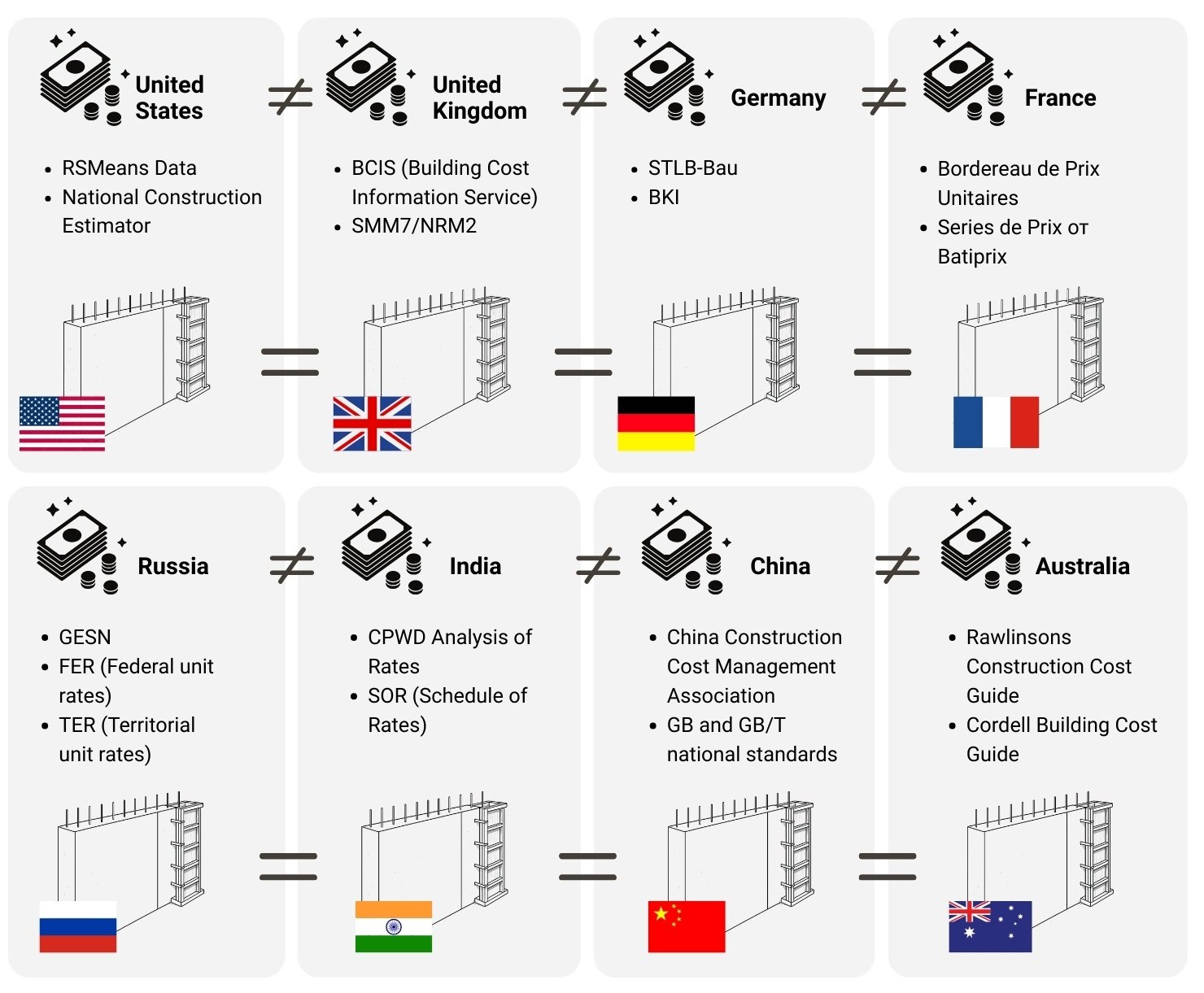

In some countries, such costing templates, accumulated over decades, are standardized at the national level and become part of the national standards of the construction costing system (Fig. 5.1-7).

Such standardized resource bases of estimates (Fig. 5.1-7) are mandatory for use by all market participants, first of all, when implementing projects with public funding. Such standardization ensures transparency, comparability and fairness in the formation of prices and contractual obligations for the customer