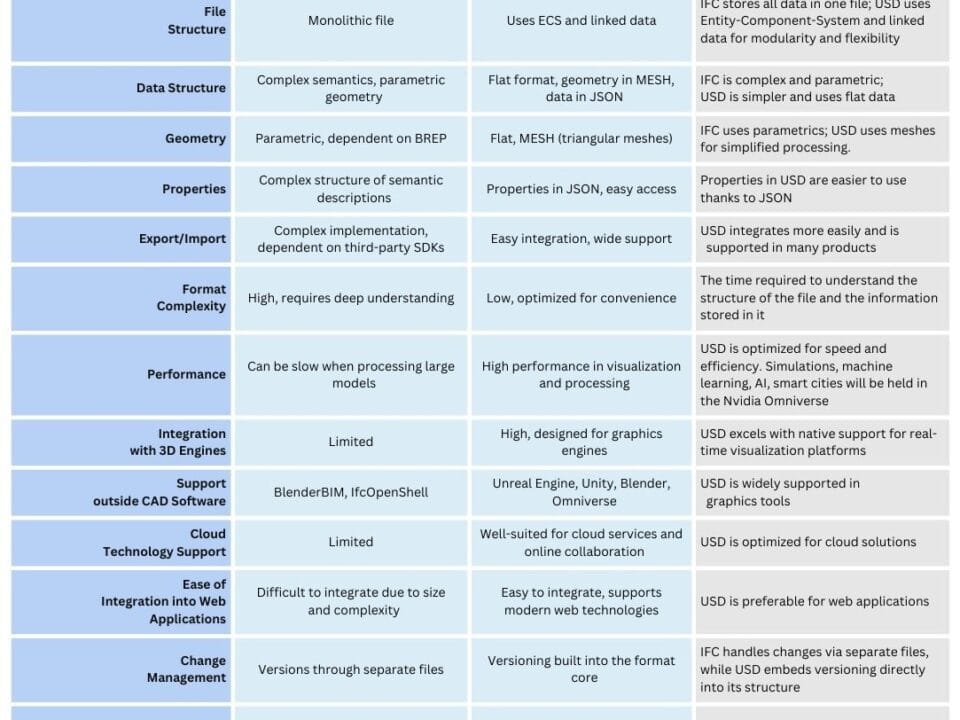

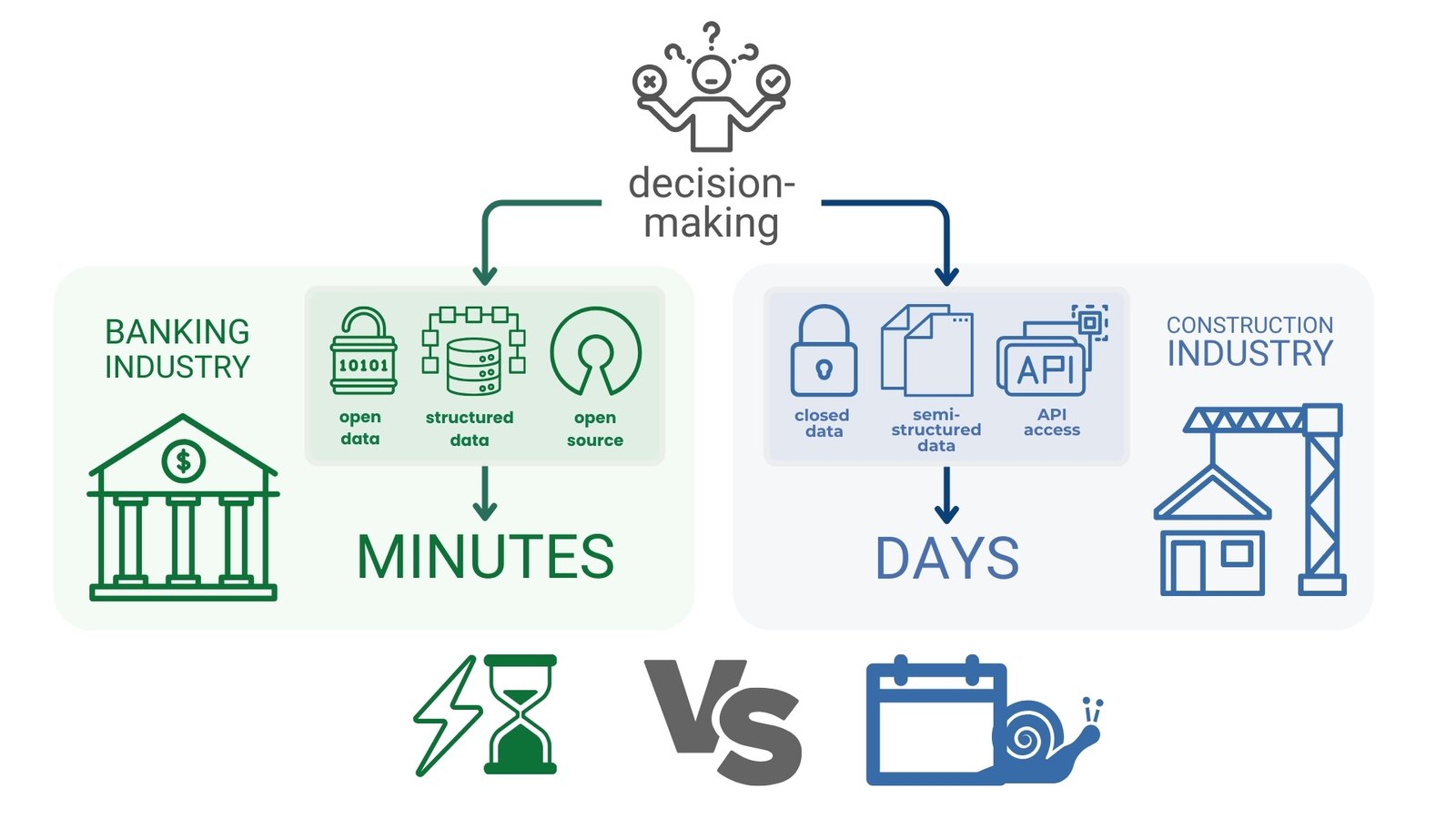

The proprietary nature of CAD -systems has led to the fact that each program has its own unique data format, which is either closed and inaccessible from the outside – RVT, PLN, DWG, NDW, NWD, SKP, or is available in semi-structured form through a rather complex conversion process – JSON, XML (CPIXML), IFC, STEP and ifcXML, IfcJSON, BIMJSON, IfcSQL, CSV etc..

Different data formats that can store the same data about the same projects not only differ in structure, but also include different versions of internal markup that developers need to consider to ensure application compatibility. For example, a CAD format from 2025 will open in a CAD program from 2026, but the same project will never open in all versions of the CAD program that may have been available before 2025.

By not providing direct access to databases, a software vendor in the construction industry often creates its own unique format and tools that a professional (design engineer or data manager) must use to access, import and export data.

As a consequence, vendors of basic CAD (BIM) and related solutions (e.g. ERP/PMIS) are constantly raising prices for using the products, and ordinary users are forced to pay a “commission” at each stage of data transfer by formats (А. Boiko, “Lobbykriege um Daten im Bauwesen | Techno-Feudalismus und die Geschichte von BIMs,” 2024): for connecting, importing, exporting and working with data that users have created themselves.

The cost of accessing data in cloud storage from popular CAD – (BIM-) products will reach $1 per transaction in 2025 (“Flex token cost,” 2024), and subscriptions toconstruction ERP -products for medium-sized companies reach five- and six-Fig. sums per year (А. Boiko, “Forget BIM and democratize access to data (17. Kolloquium Investor – Hochschule – Bauindustrie),” 2024)

The essence of modern construction software is that it is not automation or increased efficiency, but the ability of engineers to understand a particular highly specialized software that affects the quality and cost of construction project data processing, as well as the profits and long-term survival of companies undertaking construction projects.

The lack of access to databases CAD -systems that are used in dozens of other systems and hundreds of processes (А. Boiko, “Lobbykriege um Daten im Bauwesen | Techno-Feudalismus und die Geschichte von BIMs,” 2024), and the resulting lack of quality communication between individual professionals has led the construction industry to the status of one of the most inefficient sectors of the economy in terms of productivity (McKinsey, “Delivering on construction productivity is no longer optional,” August 9, 2024).

Over the last 20 years of CAD- (BIM-) design applications, the emergence of new systems (ERP), new construction technologies and materials, the productivity of the entire construction industry has dropped by 20% (Fig. 2.2-1), while the overall productivity of all sectors of the economy that do not have major problems accessing databases and marketing-like BIM concepts has increased by 70% (96% in the manufacturing industry) (D. Hill, D. Foldesi, S. Ferrer, M. Friedman, E. Loh, and F. Plaschke, “Solving the construction industry productivity puzzle,” 2015).

However, there are also isolated examples of alternative approaches to creating interoperability between CAD solutions. Europe’s largest construction company with the SCOPE project (“SCOPE – Projektdatenumgebung und Modellierung multifunktionaler Bauprodukte mit Fokus auf die Gebäudehülle,” 1 Jan. 2018), started back in 2018, demonstrates how it is possible to go beyond the classical logic of CAD- (BIM-) systems. Instead of trying to subjugate IFC or relying on proprietary geometry kernels, SCOPE developers use APIs and SDKs reverse engineering to extract data from various CAD programs, convert them into neutral formats such as OBJ or CPIXML based on the only Open Source geometry kernel OCCT, and further apply them to hundreds of business processes of construction and design companies. However, despite the progressiveness of the idea, such projects face the limitations and complexity of free geometry kernels and they still remain part of closed ecosystems of one company that reproduce the logic of monovendor solutions.

Due to the limitations of closed systems and differences in data formats, as well as the lack of effective tools for their unification, companies that have to work with CAD formats are faced with the accumulation of significant amounts of data with varying degrees of structure and closedness. These data are not used properly and disappear in archives, where they remain forever forgotten and unused.

Data obtained through significant effort in the design phase becomes inaccessible for further use due to its complexity and closed nature.

As a result, over the past 30 years, developers in the construction industry have been forced to face the same problem over and over again: each new closed format or proprietary solution generates the need to integrate with existing open and closed CAD systems. These constant attempts to provide interoperability between different CAD and BIM solutions only serve to complicate the data ecosystem, instead of contributing to its simplification and standardization.