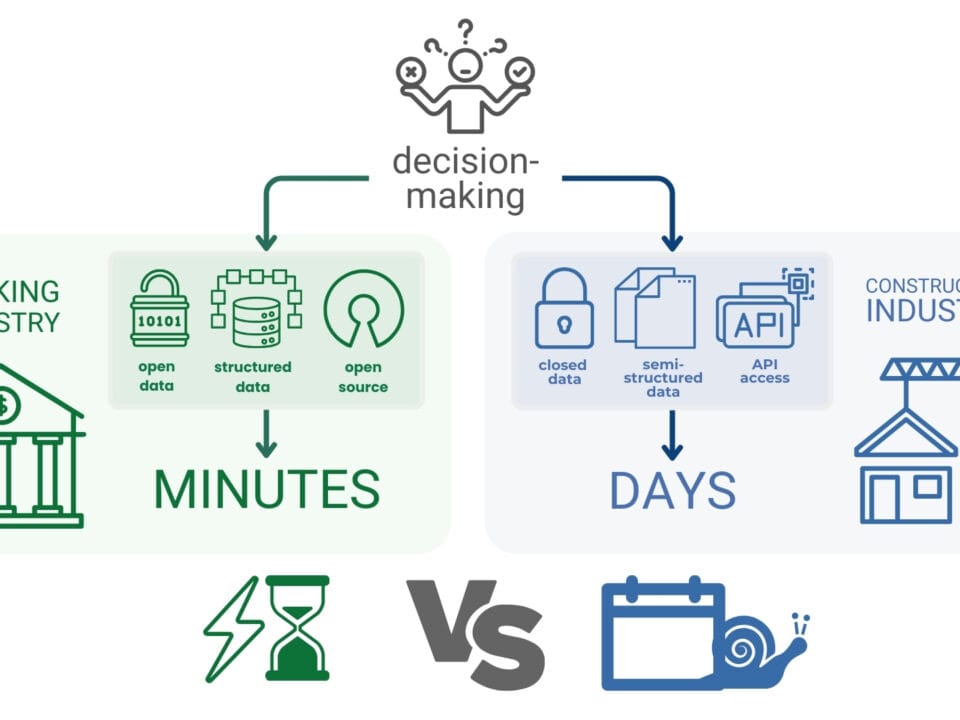

If in the mid-1990s the key direction of interoperability development in the CAD environment was the breaking of the proprietary DWG format – culminating in the victory of the Open DWG alliance (А. Boiko, “The struggle for open data in the construction industry. The history of AUTOLISP, intelliCAD, openDWG, ODA and openCASCADE,” 15 05 2024) and the actual opening of the most popular drawing format for the entire construction industry – then by the mid-2020s the focus has shifted. A new trend is gaining momentum in the construction industry: numerous development teams are focused on creating so-called “bridges” between closed CAD systems (closed BIM), IFC format and open solutions (open BIM). Most of these initiatives are based on the use of the IFC format and the OCCT geometry kernel, providing a technical bridge between disparate platforms. This approach is seen as a promising direction that can significantly improve data exchange and interoperability of software tools.

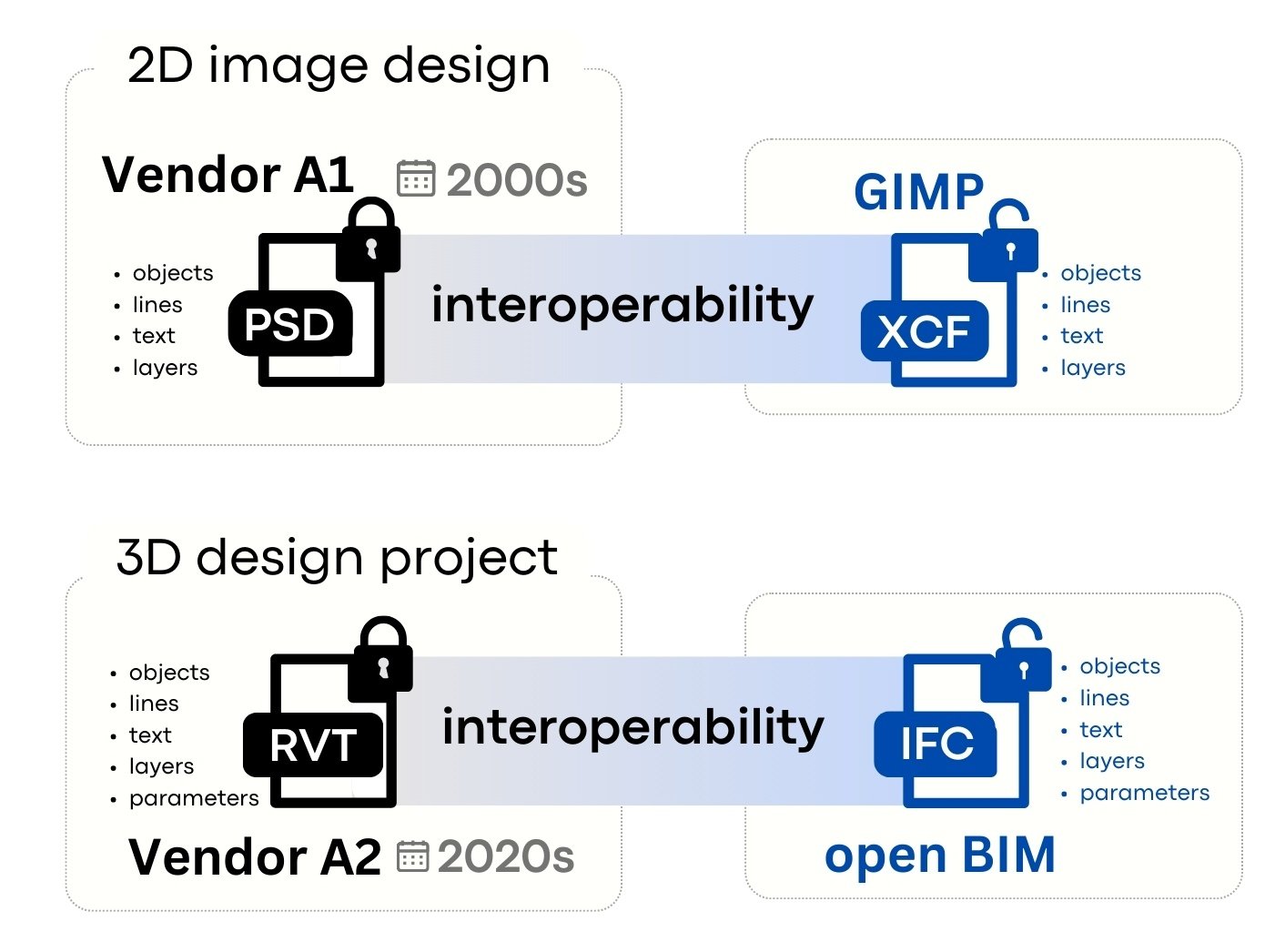

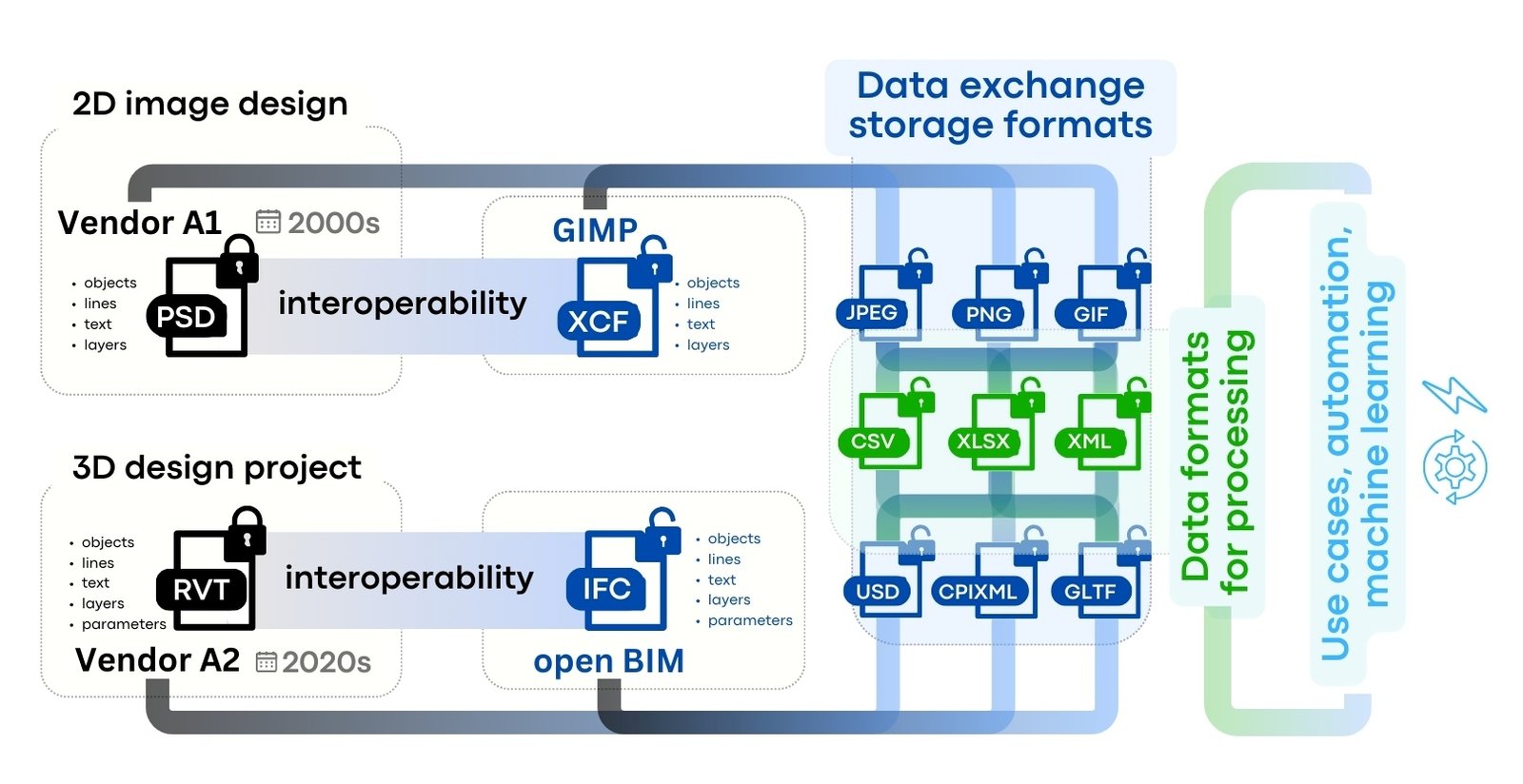

This approach has historical parallels. In the 2000s, developers, trying to overcome the dominance of the largest vendor of graphic editors (2D world), tried to create a seamless integration between its proprietary solution and free Open Source – an alternative to GIMP (Fig. 6.2-3). Then, as today in construction, it was about trying to connect closed and open systems while preserving complex parameters, layers and internal logic of software operation.

However, users were actually looking for simple solutions – flat, open data without excessive complexity of layers and program parameters (analogous to the geometric core in CAD). Users sought simple and open data formats, free from excessive logic. JPEG, PNG and GIF became such formats in graphics. Today they are used in social networks, websites, applications – they are easy to process and interpret, regardless of the platform or software vendor.

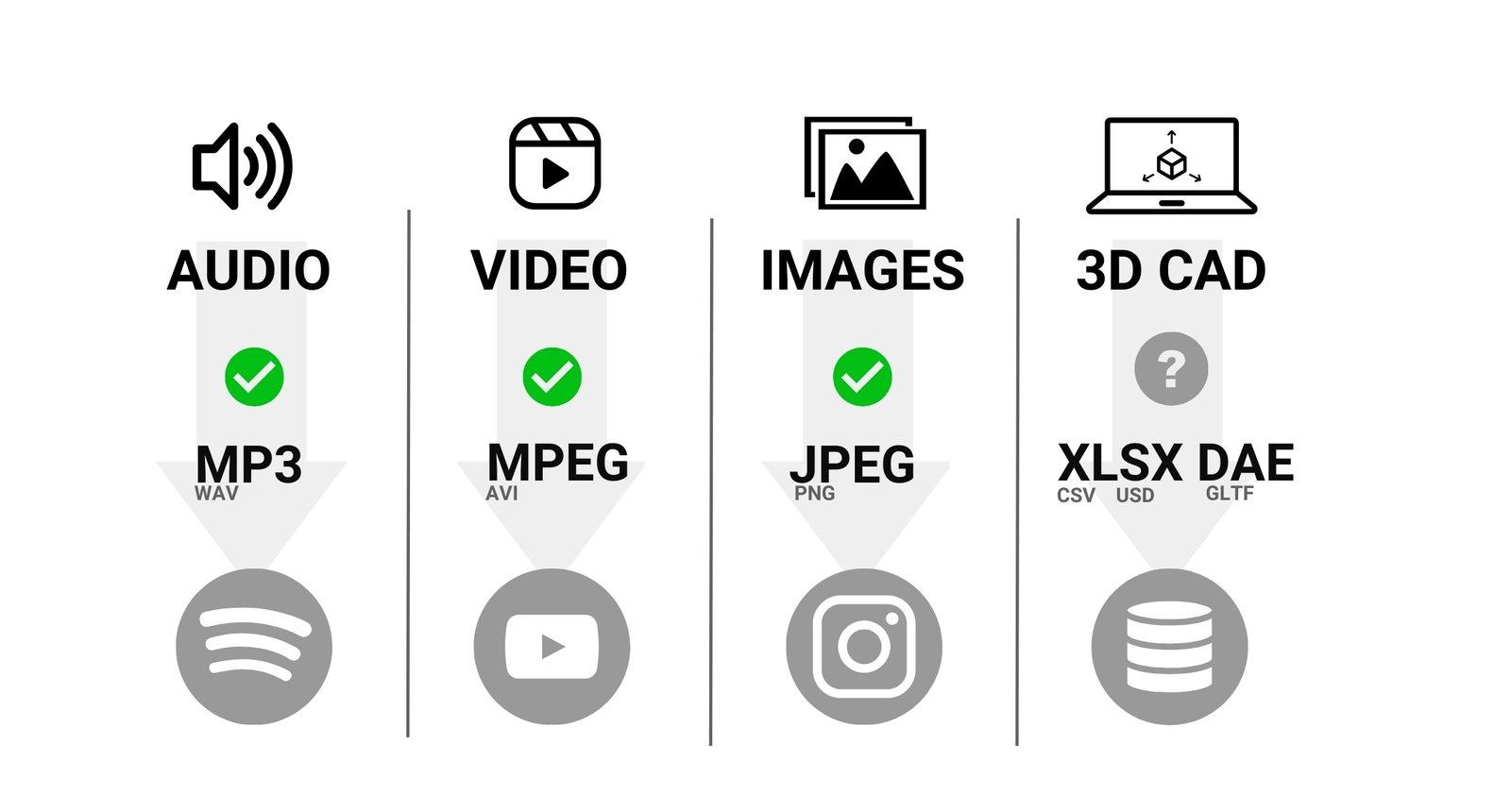

As a result, almost no one in the imaging industry today uses closed formats like PSD or open XCF for applications, social networks like Facebook and Instagram, or as content on websites. Instead, most tasks utilize flat and open JPEG, PNG and GIF formats for ease of use and broad compatibility. Open formats such as JPEG and PNG have become the standard for image sharing due to their versatility and broad support, making them easy to use on a variety of platforms. A similar transition can be seen in other exchange formats, such as video and audio, where universal formats like MPEG and MP3 stand out for their compression efficiency and broad compatibility. Such a move towards standardization has simplified the exchange and playback of content and information, making them accessible to all users across platforms (Fig. 6.2-4).

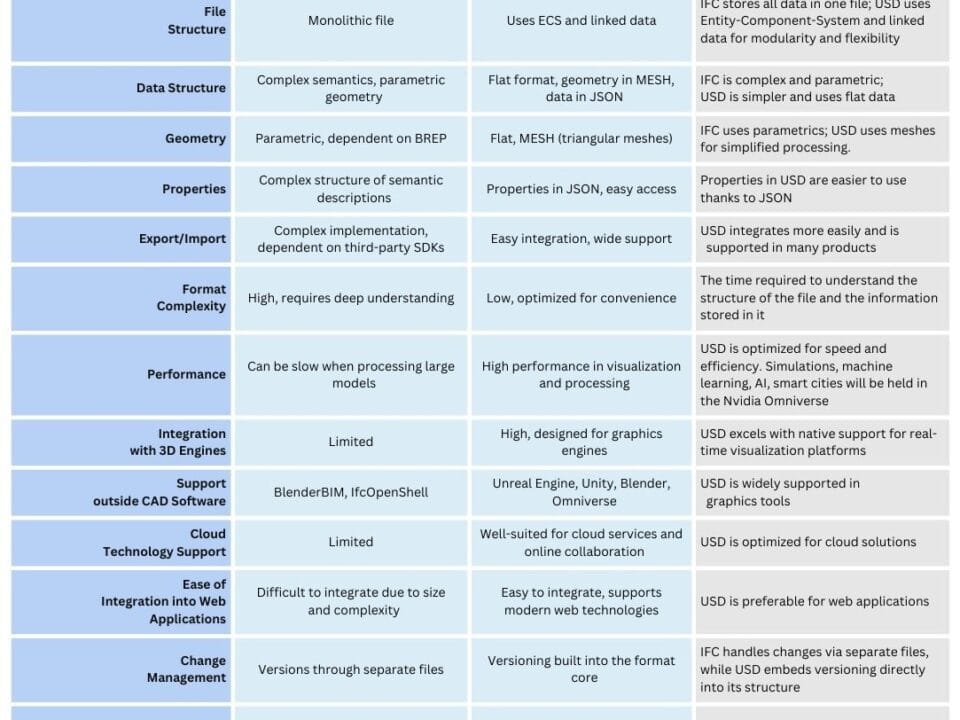

Similar processes occur in 3D modeling. Simple and open formats like USD, OBJ, glTF, DAE, DXF, SQL and XLSX are increasingly used in projects for data exchange outside the CAD environment (BIM). These formats store all the necessary information, including geometry and metadata, without the need to operate a complex BREP structure, geometry kernels or vendor-specific internal classifiers. Proprietary formats such as NWC, SVF, SVF2, CPIXML and CP2 provided by leading software vendors also perform similar functions, but remain closed, unlike open standards.

It is noteworthy (and worth recalling again, as already mentioned in the previous chapter) that this idea – the rejection of intermediate neutral and parametric formats like IGES, STEP and IFC – was supported back in 2000 by the major CAD vendor that created the BIM Whitepaper and registered the IFC format in 1994. In the 2000 Whitepaper “Integrated Design and Manufacturing” (ADSK, “Integrated Design-Through-Manufacturing: Benefits and Rationale”) the CAD vendor emphasizes the importance of native access to the CAD database within the software environment, without the need to use intermediate translators and parametric formats, in order to maintain the completeness and accuracy of the information.

The construction industry has yet to agree either on tools to access CAD databases or their forced reverse engineering, or on the adoption of a common simplified data format for use outside CAD platforms (BIM). For example, many large companies in Central Europe and German-speaking regions operating in the construction sector use the CPIXML format in their ERP-systems (А. Boiko, “Forget BIM and democratize access to data (17. Kolloquium Investor – Hochschule – Bauindustrie),” 2024). This proprietary format, which is a kind of XML, combines CAD (BIM) project data, including geometric and metadata, into a single organized simplified structure. Large construction companies are also creating new formats and systems of their own, as in the SCOPE project, which we discussed in the previous chapter

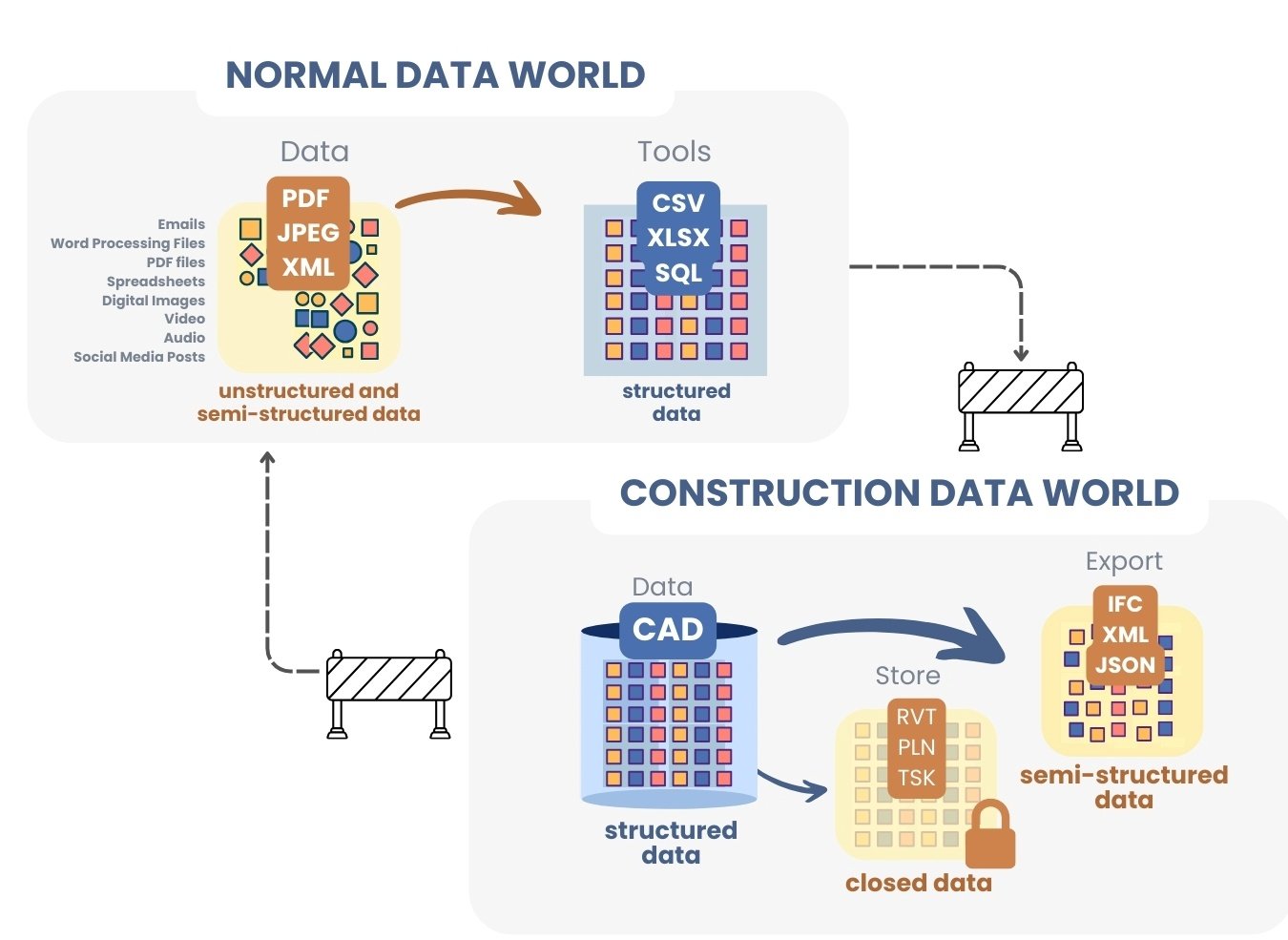

The closed logic of parametric CAD formats or complex parametric files IFC (STEP) are redundant in most business processes. Users are looking for simplified and flat formats such as USD, CPIXML, XML &OBJ, DXF, glTF, SQLlite, DAE &XLSX, which contain all the necessary element information, but are unencumbered by redundant BREP geometry construction logic, dependency on geometry kernels and internal classifications of specific CAD and BIM -products (Fig. 6.2-5).

The advent of flat image formats such as JPEG, PNG and GIF, free from the redundant logic of vendors’ internal engines, has fostered the development of thousands of interoperable solutions for processing and utilizing graphics. This has led to a variety of applications, from retouching and filtering tools to social media platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat and Canva, where this simplified data can be utilized without being tied to a specific software developer.

Standardization and simplification of design CAD -formats will stimulate the emergence of many new convenient and independent tools for working with construction projects.

Moving away from complex vendor application logic tied to closed geometry kernels and moving to universal open formats based on libraries of simplified elements creates the prerequisites for more flexible, transparent and efficient data handling. This also opens up access to information for all participants in the construction process – from designers to customers and maintenance services.

Nevertheless, it is highly likely that in the coming years CAD vendors will attempt to shift the debate about interoperability and access to CAD databases again. It will already be about “new” concepts – such as granular data, intelligent graphs, “federated models,” digital twins in cloud repositories – as well as the creation of industry alliances and standards that continue the path of BIM and open BIM. Despite the attractive terminology, such initiatives may once again become tools to retain users within proprietary ecosystems. One example is the active promotion of the USD (Universal Scene Description) format as the “new standard” for cross-platform CAD (BIM) collaboration from 2023.